Research: Fundamentalism, SOGICE and Higher Education

Paper presented at the American Sociological Association 2025 Conference

UPDATE (10/27/2025): I had previously included only a sample of the target population for this paper. Now, I’ve finished the complete categorization of my dataset. See the complete version here: sogice.com

For this year’s ASA conference, I presented a working paper on predicting “SOGICE discourse” by identifying “fundamentalism discourse.”

Here’s the why behind the need for this sort of prediction power:

SOGICE is associated with negative social and health outcomes, and the resources required for the wellbeing of SOGICE survivors is a $9 billion dollar per year public health cost, truly a public health crisis (Forsythe et al. 2022:493).

However, while “change efforts” is a broad term, it is difficult to determine the scope for SOGICE studies — methodologies are not always clear concerning what “counts” as SOGICE. Further, not all researchers may be familiar with the “inside baseball” of SOGICE discourse, which may include purposeful obfuscation strategies for legal, public perception, or funding reasons, as well as niche theological debates or discussions. Because of these difficulties, it can be helpful to correlate potential SOGICE discourse with related “frames” for analysis.

What is SOGICE? It’s an acroynm that stands for “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Change Efforts”:

“Sexual orientation” refers to “refers to the gender to which an individual is emotionally (romantically) and physically (sexually) attracted” (Longe 2022:1082), “gender identity” refers to one’s understanding of their “1) physical, 2) social/cultural, and 3) internal/sensate” masculine-ness or feminine-ness (or something outside this binary)(Skolnik and Price 2017:2), and “Change Efforts,” in this specific and particular context, refer to interventions that seek to change individuals’ attractions or sense of self to fit heterosexual and cisgendered norms (Sipling 2024:1).

And, what is fundamentalism — and in this case, the particular target of Christian Fundamentalism?

Christian fundamentalism subscribes to a belief system and is bound to a worldview which describes the Holy Bible as infallible, free from all errors, and true “in all it affirms” (Mohler 2013, p. 36), in part as a response to perceived theological and ethical liberalism (Antoun 2010). This fairly recent viewpoint, known as Biblicism (Smith 2012), also includes the doctrine of perspicuity, which states that Christian Scripture must be able to be understood by any and all readers, regardless of cultural, linguistic, or historical barriers that would normally apply to the hermeneutics of ancient texts (Richards and O’Brien 2012; Thompson 2016). … From this [fundamentalist] perspective, to make use of [science] would be to deny the doctrines of inerrancy and perspicuity, as innovations within evidence-based approaches could render the Bible lacking in “everything needed for life and godliness” (2 Peter 1:3, New Revised Standard Version, emphasis added). (Sipling 2020:933)

Fundamentalism can therefore be understood to include doctrines such as 1) infallibility, 2) biblicism, 3) perspicuity, and 4) inerrancy. These are not exclusive terms, which are essential to a fundamentalist viewpoint, but in statements of faith — which are often succinct and pithy documents — “dictionary definitions” of these doctrines can be straightforwardly identifiable.

The hypothesis is this: if you see “fundamentalism” in an organization — in a statement of faith, employee handbook, code of conduct, etc. — you’ll likely find SOGICE there, too. How does that play out in a particular field test?

This test investigates whether a fundamentalist statement of faith predicts the presence of SOGICE discourse in institutional policies and official materials. To assess this relationship, a structured content analysis is performed on statements of faith (or supplemental policies), and the presence of SOGICE discourse between fundamentalist and non-fundamentalist institutions is compared.

The sample of institutions is drawn from the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) directory, which provides a comprehensive listing of accredited theological institutions in the U.S. and Canada.

My inclusion criteria were that schools drawn from this pool are that the schools must be 1) Christian and 2) Protestant. It’s not that fundamentalism doesn’t exist in other religions; it’s that we have operationalized identification criteria for this particular sub-group. And for criteria 2:

Because Protestant organizations do not answer to…. authoritative magisterial teaching as Orthodox, Catholic, and other ancient or apostolic churches do, they allow for a range of interpretations and beliefs that include fundamentalism (or not), and SOGICE discourse (or not).

The Test

For the categorization criteria, each ATS school is categorized as fundamentalist or non-fundamentalist based on publicly available statements of faith, as found on webpages, within codes of conduct, or employee handbooks. Criteria for categorization include explicit affirmations of infallibility, biblicism, perspicuity, and inerrancy, and restrictive theological positions on gender and sexuality which logics are grounded in infallibility, biblicism, perspicuity, and inerrancy. To assess the presence of SOGICE discourse, statements of faith (supplemented by other institutional documents or policies, as needed) were systematically analyzed for indicators of fundamentalism and SOGICE. A keyword-based search and qualitative coding approach was used

And here were our results:

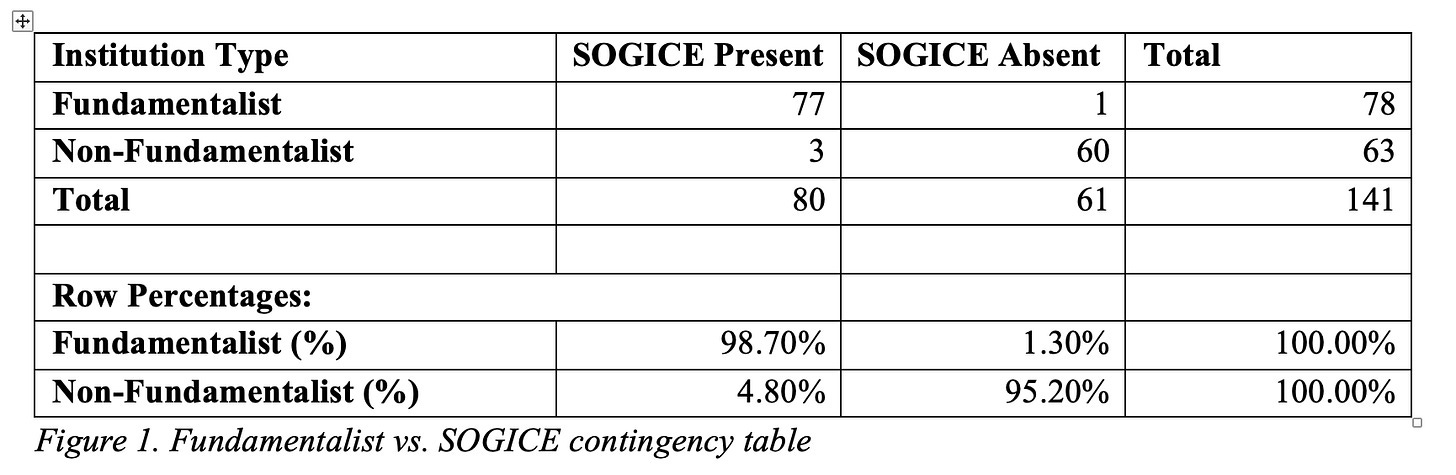

The content analysis compared the rate of SOGICE discourse between fundamentalist and non-fundamentalist schools. Due to time constraints, a sample of 141 of the 220 institutions (for a 95% confidence level and 0.05 margin of error) was analyzed. The conclusion is that the presence of fundamentalist discourse is an excellent predictor of SOGICE discourse.

From this sample of 141 schools, 78 institutions (55.3%) demonstrated fundamentalist discourse and 80 institutions demonstrated SOGICE discourse (56.7%). Among the 78 fundamentalist institutions, 77 exhibited SOGICE discourse; among the 63 non-fundamentalist institutions, 3 contained SOGICE discourse. This demonstrates a conditional prevalence of 98.7% among fundamentalist versus 4.8% of non-fundamentalist institutions… Chi-square analysis demonstrated a significant association between fundamentalist and SOGICE discourses (χ²(1) = 125.34, p < 0.001). A large effect size, indicated by Cramér’s V = 0.943, indicates a relationship of substantial magnitude.

Given this, we see that:

Fundamentalist theological markers serve as highly reliable predictors of institutional policies aligned with conversion therapy ideology and anti-LGBTQ+ ideology.

I don’t plan on posting this paper, as I will plan on finishing the full content analysis of the 220-school list, and thanks to some great feedback at the conference, I want to draw distinctions between “LGBTQ+ discrimination” and “SOGICE discourse,” so that’ll be an entirely new section for the finished paper.

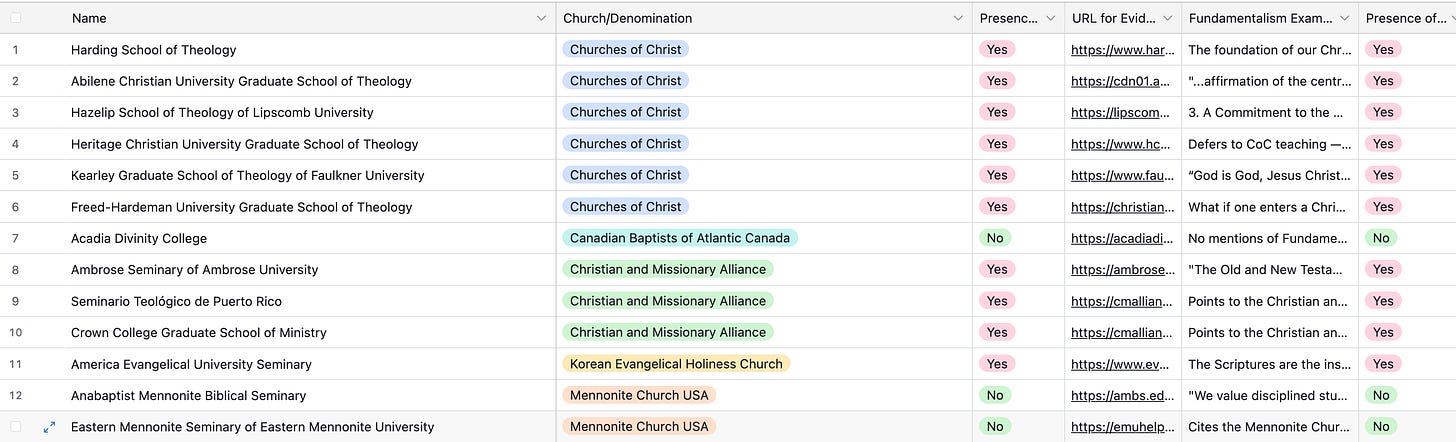

Further, I’ve put a table of the content analysis on this page: sogice.com. On that table, you can see where I’ve listed out the schools and whether or not they have fundamentalist discourse and/or SOGICE discourse. You can also use the table’s sorting and grouping functions to play around with this data, as well.

But, in terms of identifying frames to then identify SOGICE more effectively, here’s at least one test — hopefully, among the first of many more! — that demonstrates this method can be somewhat useful.